Reflecting on the tenets that shape our educational practices is fundamental for …

Over 1,000 Native Children Found to Have Died in Federal Boarding Schools

Emma Wordsmith

Close to 1,000 Native American children lost their lives or were victims of violence while being compelled to attend U.S. government-connected boarding schools, as confirmed by a report by the Interior Department.

In 74 designated and unmarked graves, these children rest, prompting tribes to contemplate repatriation of remains and protective measures over fifty years following the shift in U.S. policy away from the practice. An estimated count of nearly 19,000 children were forcibly separated from their families, at times under threat of violence, and enrolled in government schools with the intent of erasing their cultural identities, damaging tribal traditions, and curtailing land ownership.

Although the department acknowledged that the numbers are likely an understatement, the data marks the most comprehensive assessment of the extent of the system, wrapping up a three-year project to uncover the toll and legacies of the nearly two-century-long U.S. policy. Historical research faced obstacles due to inconsistent public record keeping and the privatization of records by religious institutions.

At 65 schools and their adjacent communities, the remains of 973 children were located, but the Department has decided to withhold their specific locations “to prevent against documented grave robbery, vandalism, and other disturbances to Native burial sites.”

The recently released final report also delved into the detrimental effects of the boarding school system on the health outcomes and genetics of Native families, who have continued to experience high rates of substance abuse, suicidal thoughts, and chronic illnesses like diabetes, arthritis, and cancer for generations.

“As we have discovered over the past three years, these institutions are not confined to our history,” noted Assistant Secretary of the Interior Bryan Newland in the introductory letter of the report. “Their impact is still felt today and is evident in the ongoing suffering in communities throughout the United States.”

Vivid accounts from numerous survivors of the atrocities, many shared for the first time during the Road to Healing tour, detailed horrifying instances of physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.

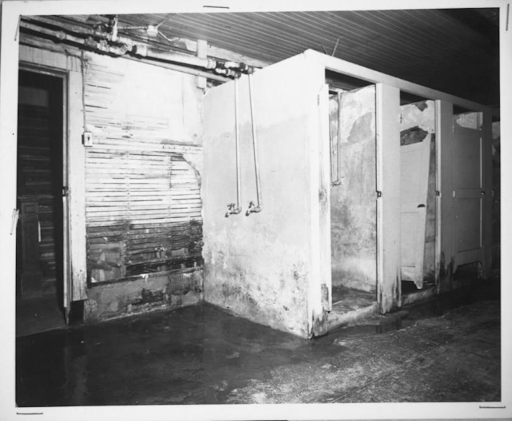

There were distressing reports of children witnessing the abuse of their peers, with incidents of rape by priests, teachers, and school personnel occurring in their beds and restrooms. Disturbingly, children as young as 11, 12, or 13 were sent home during the school year pregnant.

In one Montana school, night checks were implemented, during which flashlights were shone randomly into the children’s eyes as they slept. Some children were relegated to sleep in basements as a form of punishment, only to be forgotten for hours or days. Numerous others were sent outdoors to live temporarily with neighboring white families, mainly Quakers, and were exploited for unpaid labor.

“The most unbearable part was at night, hearing the other children cry themselves to sleep, longing for their parents and yearning to return home,” recounted a survivor from Michigan. “I remember one girl who wet the bed; they made her scrub the entire bathroom on her hands and knees with her toothbrush.”

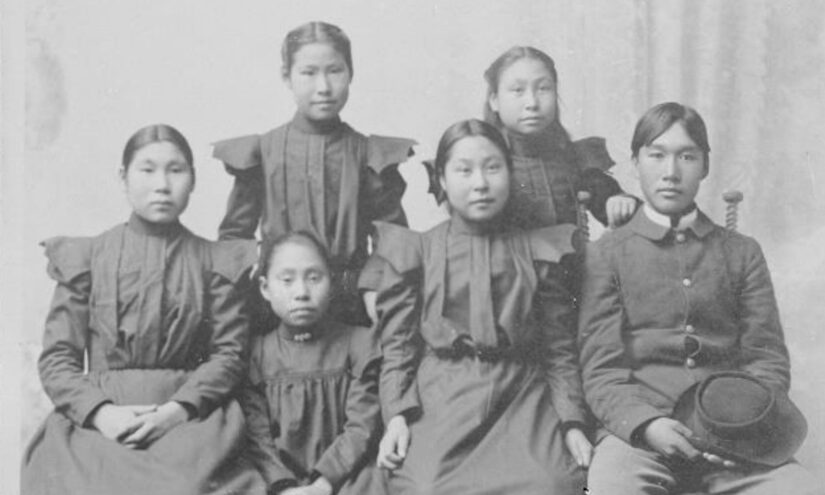

Upon arrival, children were often stripped of their clothing, had their hair forcibly cut—contrary to sacred cultural beliefs—issued uniforms, and assigned identification numbers.

“We were never called by our names, only by our assigned numbers. Mine was 77 because my sister was there before me, and her number was also 77. The number was marked on all our belongings,” shared a survivor from Alaska.

Separated by vast distances from their homes and with limited chances of escape, children witnessed the eradication and substitution of every aspect of their former identities and lives—religious beliefs, language, hairstyle, and attire.

“Food was weaponized within the Indian boarding school settings, drastically contrasting traditional Native American views of food as medicine,” as highlighted in the report. “Any food perceived by Federal Indian boarding school staff as reminiscing of Native American culture was prohibited, and survivors frequently recounted being compelled to consume highly processed, unfamiliar, or spoiled food.”

An Alaskan survivor detailed the consequences of abruptly transitioning to consuming processed, canned meats and vegetables, powdered milk, and eggs. “We became violently ill because our bodies couldn’t adapt to the sudden change in our diet from our traditional Native foods. We experienced vomiting, diarrhea, or both and were often chastised for soiling our clothes or bedding and physically punished for it.”

Between 1871 and 1969, over $23 billion, adjusted for 2023 inflation rates, was channeled into the federal Indian boarding school program. Excluded from this figure are estimates related to child labor that were intended to reduce operational expenses, as children frequently undertook tasks like maintaining school facilities, plumbing excavation, or roof upkeep.

A total of 417 schools, with 210 under the administration of predominantly Protestant or Catholic religious organizations, were operated and funded by the U.S. government across 37 states and territories.

The ultimate numbers of fatalities and enrollments do not encompass records from the 1,025 “other institutions,” including day schools and orphanages that were not federally supported, where children experienced similar maltreatment in furtherance of the government’s explicit objective of mass assimilation.

Reflecting on her time in boarding school, a survivor from Minnesota lamented, “I was told I wouldn’t make a good mother. I promised God that when I have children, I will love them, care for them, and treat them with dignity, since in boarding school, you’re dehumanized. You’re not even considered a person.”

Defiance was common, with instances of runaways, surreptitious use of local languages, and resistance when government agents invaded reservation lands to seize children.

A year after 104 children were taken from the Third Mesa of Hopi to attend Keams Canyon Boarding School, Hopi tribal leaders refused to yield to armed government agents. As a consequence, nineteen leaders were detained as prisoners of war and incarcerated in an underground cell on Alcatraz.

Even after the decline in political favor of the residential boarding school system, forced removal persisted through the Indian Adoption Project from 1958 to 1968, during which up to 35% of Native children were taken from their families following discriminatory welfare probes and predominantly placed in non-Native households.

Deliberate inequalities were apparent: In Minnesota, Native children were enrolled in foster care and adoption five times more frequently than non-Native families, while in Washington, the disparity was 19 times greater.

The practice continued until 1978 with the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act, marking the first congressional recognition that the “wholesale separation of Indian children from their families is perhaps the most tragic and destructive aspect of American Indian life today.” The Act condemned forced child removal and cultural assimilation.

Last year, the Indian Child Welfare Act faced a challenge in the Supreme Court after white families, who had already secured custody to adopt a Cherokee and Navajo child over a Navajo family, in opposition to the Act’s stipulations to emphasize cultural-consistent adoptions, filed a federal lawsuit alleging discrimination. Three additional white couples joined the litigation. The court ultimately upheld the Indian Child Welfare Act in a 7-2 majority decision. All the children had Native relatives seeking custody, but only one Ojibwa grandmother, after a six-year struggle, gained custody of the children.

Prioritizing reconciliation with tribal nations, the report advocated for investments in family reunification, education, language revitalization, identification and return of children’s remains, healthcare, and the establishment of public memorials or educational initiatives to disseminate information about the former system.

Several residential schools are operational nowadays without the assimilationist agenda or systemized violence. A proposed Senate bill, supported by both parties, is on the brink of a vote to institute a truth and healing commission and three advisory committees over a six-year span, an action that Native leaders have lauded as “long overdue.” Members representing at least seven tribes in Arizona and New Mexico are now permitted to file claims against the Franciscan Friars of California for clergy sexual misconduct.

The Interior Department Secretary, Deb Haaland, affirmed during the Road to Healing tour, “We’re not mere individuals co-inhabiting this planet; we bear a responsibility to honor our ancestors’ legacy, ensuring their suffering was not in vain, they were not sacrificed for naught, and they were not forcibly separated from their mother’s embrace without cause.”

Testimonies from survivors collected during the Interior Department’s Road to Healing tour:

“I would like to say my aunt said after we all left, after the planes came and we all left, she said the village was so quiet because there was no children. No children in the village.” – Alaska

“My sister talked about being put in the closet with the mops and the brooms. And, to this day, she can’t sleep without a light on. She could be deep in her sleep, and as soon as somebody turns off the bathroom light, she wakes up screaming. And she’s a grandmother today. She doesn’t know where this comes from.” – Washington“Sometimes they would forget that they had put us down in the basement. Wouldn’t get out of there until early morning, and it was – maybe that’s why I’m afraid of the dark now. I don’t know. I leave the light on in my bedroom. Even today. That was a – that was hurt – hard for me. I still think about those nights when I had to sit in the basement. I was afraid of the dark. And I survived there for six years.” – Montana

…They said ‘We’re going to run away and we’re going to go home and when we get home, we’ll send for you.’ … They waved to us and were just really happy… they didn’t know they were on – the school is on an island and the next morning, we went into the dining hall and they all came in … Their heads were shaven and they were all wearing little black and white prison suits and us girls just started crying.” – Alaska

“The sad part about it is a lot of us had to watch the priest sodomize our classmates … Nobody wants to share things like that. I’ve learned how to be tough because you couldn’t cry. Couldn’t do that.” – South Dakota

“They came in, they stripped them down, put all their clothes, the food they bring in, dry caribou, salmon, and stuff like that, they put it all on the side. They made them go through the shower, shave them, give them their uniform and a number … I probably cried when they took all their clothes down there and burned them in the furnace, all the beautiful, beautiful parkas and everything.” – Alaska

“My grandpa’s last words were, ‘We’re going to experience some things,’ in Cheyenne… Culturally, our hair is sacred. ‘We do not cut our hair, but they’re going to do that to you. You get there, your black braids are not going to come home.’ And that was hard. My braids got cut off. Excuse me. Just remembering what happened to some of us first day of school.” – Montana

“Once I graduated, I had to go straight to the Marine Corps because I had no parents, nobody there when I finished … to this day, I know it affected my sister, because I haven’t seen her in probably 30 years, and she’s been in and out of prison ever since. She’s never been back to the Indian reservation … I don’t have a very good relationship with my mother, because by the time we started talking again she – there’s a lot of feelings that was brought up just because of separation.” – California

“I experience feelings of abandonment because I think of my mother standing on that sidewalk as we were loaded into the green bus to be taken to a boarding school. And I can see it – still have the image of my mom burned in my brain and in my heart where she was crying. What does a mother think? She was helpless.” – Arizona

“I don’t remember ever getting a hug from my mom. I don’t remember, ever, my mother telling me she loved me. I remember getting whipped with a switch and finally being able to go live with my father because they didn’t live together anymore … He never did anything like that. He said, ‘That’s because of the schools.'” – Washington

“To this day I can still see that nun standing and she said, ‘Here,’ she gave me a bag and I said, ‘Oh, what is it?’ ‘Oh, it’s from your brother.’ ‘Oh, is he here?’ ‘No, he’s dead.’ I could still see her standing there and I was still a little girl. And I thanked her.” – Minnesota

“I said to Sister Naomi, I think I’m going to go home now. She leaned way over into my face and said, ‘You’re not going anywhere, you’re going to be here for a long, long time.’ So, I choked back my tears and I hid inside myself.” – Michigan