During this summer, a team of students from MIT embarked on a journey to the sou …

“The Pandemic’s Lifetime Tax: The Lost Generation”

Carlos Changemaker

Reports of declines in student performance due to the pandemic are now treated as old news. Amid abstract reporting of test results, a sense of inevitability and complacency has developed. After all, can we truly deem it significant that students’ math scores decreased by “nine points”?

The truth is that the cohort of students in school in March 2020 has been significantly harmed—they now face a lifetime tax on income amounting to 6 percent. And this harm is long-lasting.

One way to evaluate the loss in learning caused by the pandemic is to compare the performance of students who were tested in 2023 to those who took the same tests in 2020. The most recent data come from the National Assessment of Educational Progress for 13-year-olds. Referred to as the Nation’s Report Card, NAEP provides regular assessments of American students’ math and reading skills at various ages. By comparing the 2023 results with those of students tested just before the pandemic, we find that math scores decreased by an average of nine points and reading scores decreased by four points. These declines have effectively erased all the gains in math scores since 1990 and brought reading scores back to the level they were at in 1975! Low-achieving students experienced greater losses than high achievers, poor students lost more than nonpoor students, and both Black and Hispanic students experienced greater losses than white students.

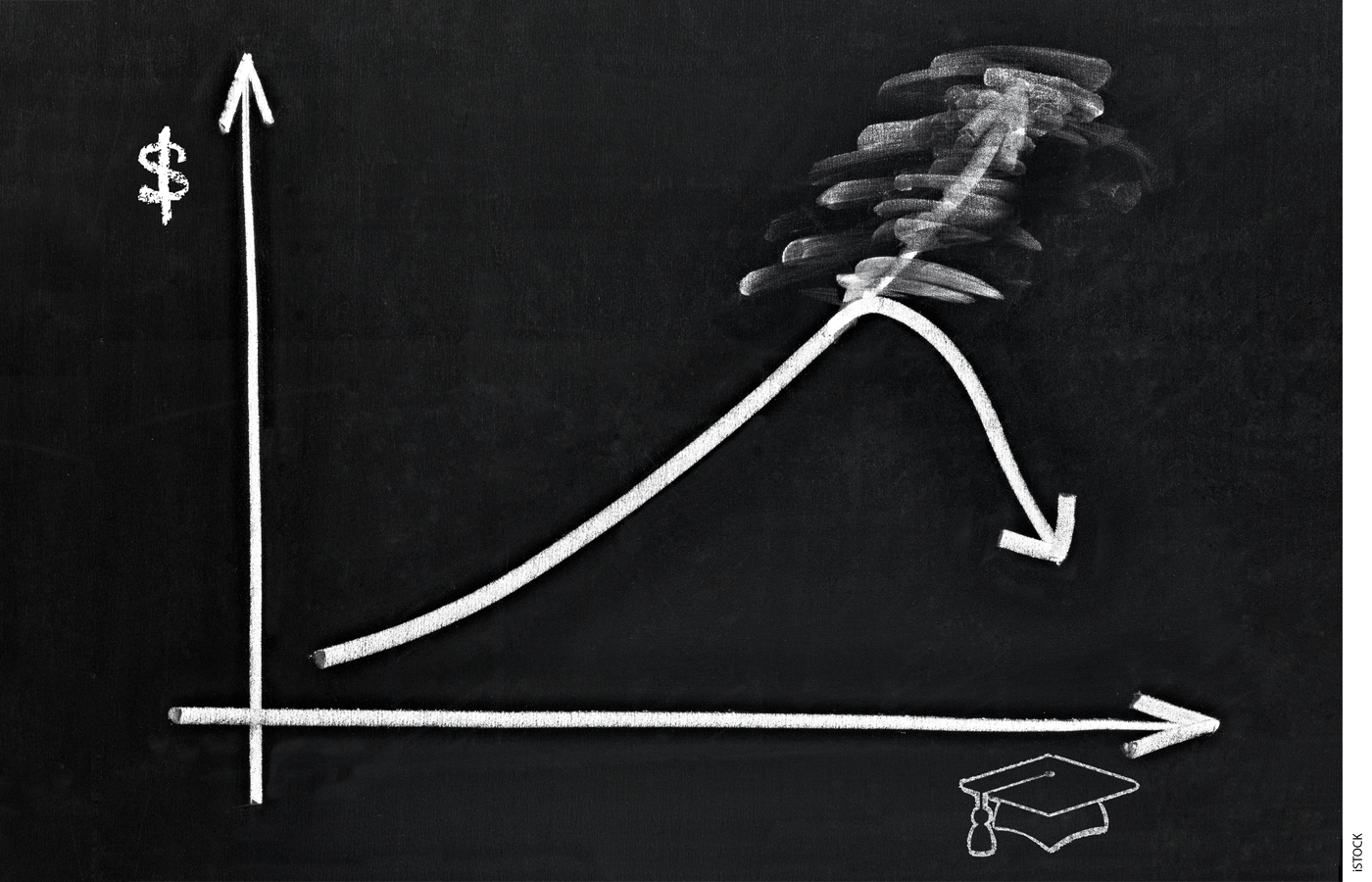

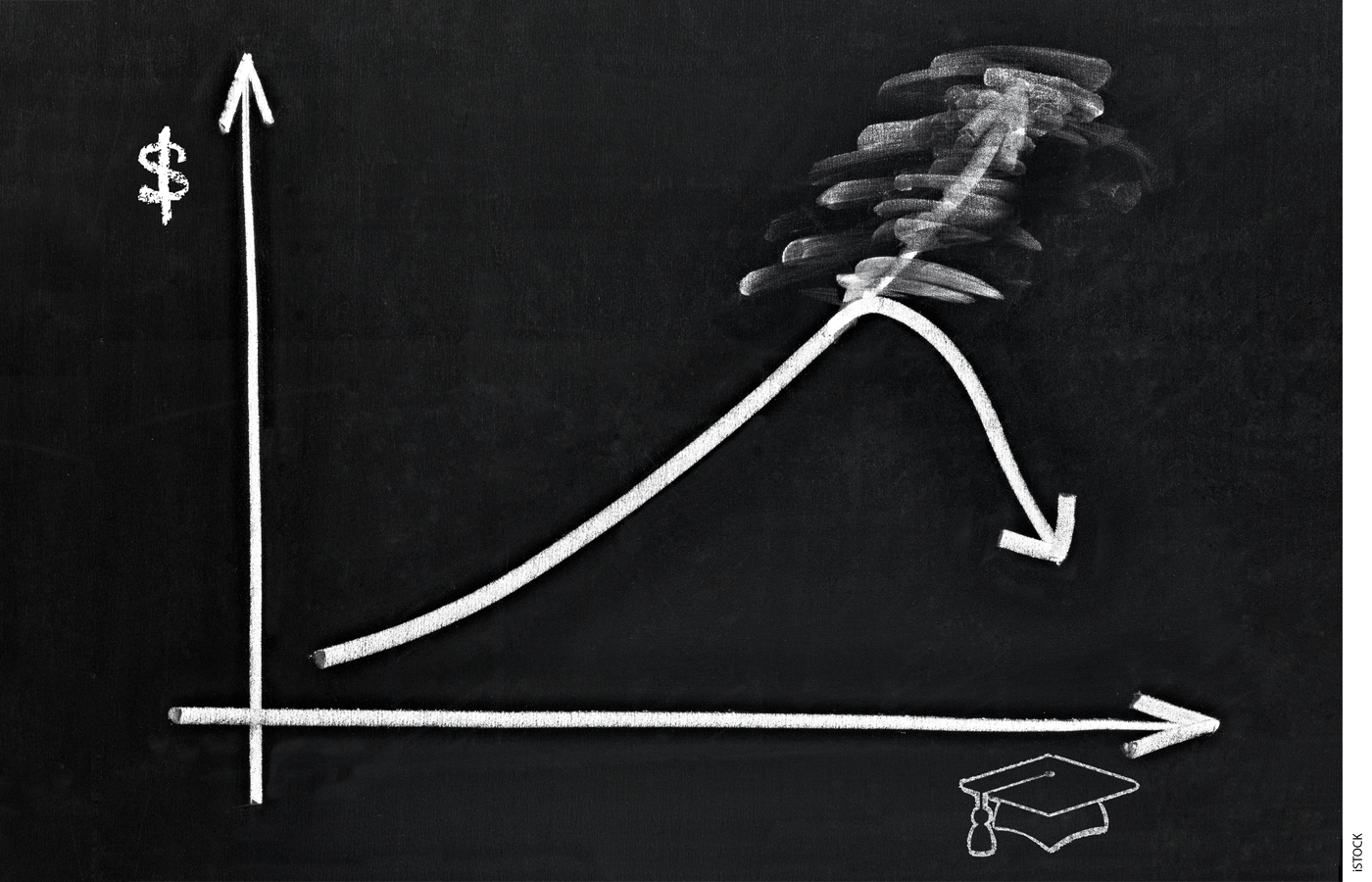

However, NAEP, like most tests, uses an arbitrary scale to report scores that makes it difficult to interpret the magnitude of changes. The impact of lost learning becomes clearer when we translate these numerical figures into economic losses. Previous research confirms that individuals with higher knowledge, as assessed by their performance on tests like NAEP, earn more. This research examines how individuals’ earnings throughout their careers differ based on the skills measured by scores on standardized math and reading tests. Crucially, the U.S. labor market values these cognitive skills more than most developed countries, which implies that the U.S. penalizes the absence of these skills more than most developed countries.

By examining historical earnings patterns, we can estimate the cost of the learning loss documented by NAEP for the average student in the Covid-cohort: their lifetime earnings will be 6 percent lower than those not in this cohort. In other words, the pandemic-induced learning losses for this cohort are equivalent, on average, to a 6 percent income tax surcharge throughout their working lives. This figure increases to 8 percent for the average Black student, who experienced greater learning losses according to NAEP.

The economic costs do not stop there. Nations with more skilled populations exhibit faster economic growth in the long run, and the learning losses caused by the pandemic suggest that the future U.S. population will have lower skill levels than it would have had otherwise. By using historical growth patterns, we can project the aggregate losses to the U.S. economy resulting from having a less skilled workforce, which amounts to $28 trillion in present value terms.

Describing costs in trillions of dollars may be just as difficult to comprehend as drops in test scores. To put this figure into perspective, consider that the projected loss of $28 trillion exceeds one year’s Gross Domestic Product. Additionally, the aggregate losses due to unemployment, business closures, and other pandemic-related economic consequences amounted to around $2 trillion. The losses from the “Great Recession” in 2008 totaled about $5 trillion. In summary, the impact on the economy that we should anticipate from pandemic-era learning loss far surpasses the impacts that have garnered significant attention from the public and policymakers in recent years.

We are currently grappling as a nation to restore our schools to the level of support they provided for student learning prior to the pandemic, but if we merely return schools to the status quo of March 2020, these costs will be permanent. Our schools must improve if we are to alleviate the burden of lost learning. Evidence from various experiences in other nations shows that the losses students have experienced persist if schools simply operate as they did before. For example, several German states had shortened school years in the 1960s when policymakers aimed to standardize school calendars nationwide. The earnings of students educated during that period deviate from those of students educated before and after the change, and not in a positive manner. Furthermore, other instances of prolonged school disruptions, such as those due to extended teacher strikes, yield similarly enduring impacts.

What has been done so far to address learning loss? The federal government has allocated nearly $190 billion in Covid relief aid to schools through three separate appropriations. However, only a small portion of these funds was obligated to be spent on mitigating learning loss, and most schools have yet to utilize much of these funds even though they will expire within a year.

States and districts have implemented various strategies, with the most common ones involving increased instructional time or intensive tutoring. Unfortunately, the outcomes of these efforts thus far have been unsatisfactory. Even if we assume that the best available programs will be implemented as intended, the losses cannot be completely offset. The scale of the current recovery efforts simply falls short of overcoming the deficits. Furthermore, when recovery programs are voluntary, as is often the case, higher-achieving students are more likely to participate, exacerbating the achievement gaps.

At the same time, the pandemic has reinforced several harmful policy trends that may lead to a decline in school quality. It has further accelerated the shift away from test-based accountability policies. Additionally, teacher unions have viewed the pandemic as an opportunity to advance a range of their preferred policies, extending beyond matters of compensation, benefits, or anything related to learning. For instance, the Oakland Teachers Association, despite agreeing to a substantial increase in pay and benefits, still went on an eight-day strike in May 2023 over “common good” clauses, including reparations for Black students and “environmental justice.”

There is