During this summer, a team of students from MIT embarked on a journey to the sou …

The Alexander Doctrine: Governors as Catalysts for Change

Carlos Changemaker

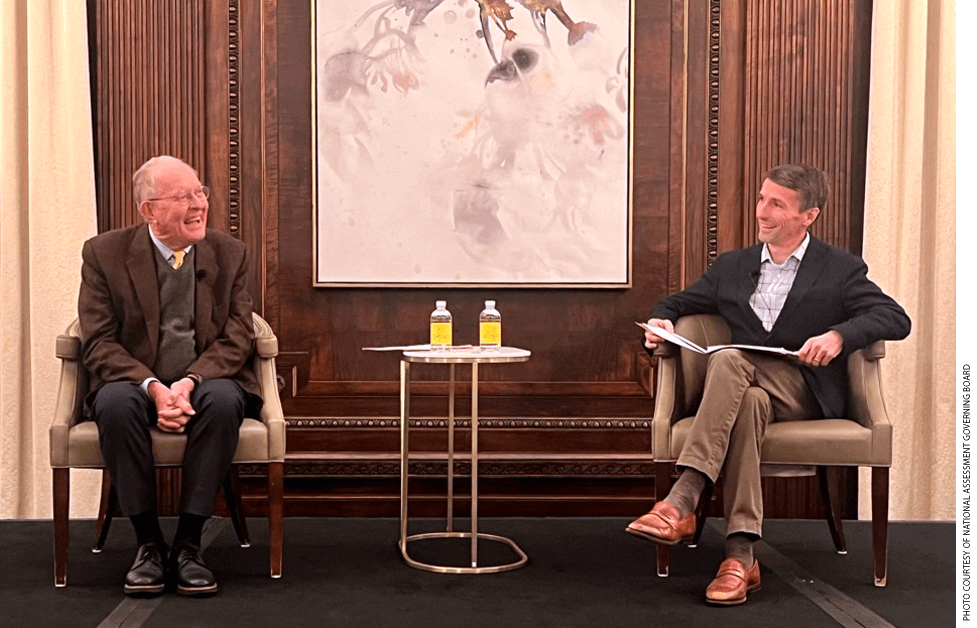

In the realm of education, the importance of engaging governors is underscored by former Tennessee Governor, U.S. Secretary of Education, and U.S. Senator Lamar Alexander, as he addressed the National Assessment Governing Board prior to their quarterly gathering in February.

Senator Alexander engaged in a dialogue with board member and Education Next editor Marty West in Nashville, Tennessee, discussing the establishment of the Governing Board 35 years ago and his emphasis on accountability, transparency, and communication in his work.

The following interview has been condensed for brevity and clarity.

Marty West: Your commitment to enhancing K–12 education stands out as a central theme in your public service career. What motivated you to focus on education initially, and what sustained your dedication over time?

Senator Lamar Alexander: My journey into education began with two key factors. Firstly, my parents both had careers in education, with my mother serving as a preschool teacher and my father as a principal. This instilled in me a deep appreciation for the value of education. Additionally, when I assumed the role of governor in 1979, Tennessee faced significant economic challenges, ranking as the third poorest state in terms of family incomes. This spurred me to explore ways to transform the state’s economic landscape by fostering a skilled workforce through improved education. The equation was clear to me: better schools equated to enhanced skills, resulting in better employment opportunities. This realization shaped my focus and eventually yielded tangible outcomes.

Subsequently, my tenure as president of the University of Tennessee underscored the transformative power of a high-quality university in uplifting a state. Following this, my appointment as education secretary under President George H.W. Bush coincided with the establishment of national education objectives in collaboration with governors and President Bush. As my Senate tenure unfolded, the pressing need to rectify issues within the education realm, particularly the shortcomings of No Child Left Behind, became apparent. Almost every school in the country was deemed subpar under NCLB’s criteria, prompting a concerted effort with President Obama, the Republican House, and Senator Patty Murray to revamp the system, resulting in the enactment of the Every Student Succeeds Act.

West: You’ve highlighted significant milestones in your career, yet the genesis of this institution remains unexplored. In 1986, you assumed leadership of a task force designated by the Secretary of Education to evaluate the National Assessment of Educational Progress. This endeavor culminated in the Alexander-James report, released in January 1987 under the title “The Nation’s Report Card.” Checker Finn, a member of the working group and inaugural NAGB chair, credits you with coining this iconic term. Can we attribute the moniker to your ingenuity?

Sen. Alexander: Given the ponderous nature of the moniker “National Assessment for Educational Progress,” I proposed the simplified, attention-grabbing title “The Nation’s Report Card” to invigorate public interest in the initiative.

West: The report’s pivotal recommendation centered on expanding assessment beyond a national scale to encompass state-level evaluations, including the District of Columbia. How did this proposition align with your vision?

Sen. Alexander: Following the release of “A Nation at Risk” during my second gubernatorial term, the necessity for state-specific evaluation became apparent. This prompted the inception of the Alexander-James Commission, advocating for state assessments and the formation of an independent oversight entity—the NAGB—culminating in the delineation of achievement levels—basic, proficient, and advanced—currently utilized. Collaborative efforts with President Reagan and Ted Kennedy saw the legislation enacted in 1988, emphasizing state and local representation devoid of federal intervention.

West: You underscored the hunger for localized data among governors in the past. Presently, states are afforded the option to partake in individual NAEP assessments such as history and civics, with minimal uptake. What does this trend signify to you in terms of gubernatorial engagement and transparency, akin to the pioneering spirit observed in Southern education governors in the 1980s?

Sen. Alexander: Oftentimes, the prioritization of American history and civics education resonates positively with constituents, translating into political currency. The receptiveness to actionable proposals among governors, premised on tangible benefits for their constituents and reelection aspirations, underscores the efficacy of localized initiatives in driving educational improvements. The dissemination of successful outcomes among governors fosters a ripple effect, stimulating broader uptake and funding allocation for impactful initiatives, extending potentially to scientific literacy.

The post The Alexander Doctrine: Governors are Agents of Change appeared firstjsonassistant