During this summer, a team of students from MIT embarked on a journey to the sou …

Campus Violence: A Barrier to Fostering Responsible Citizens

Jennifer Livingstone

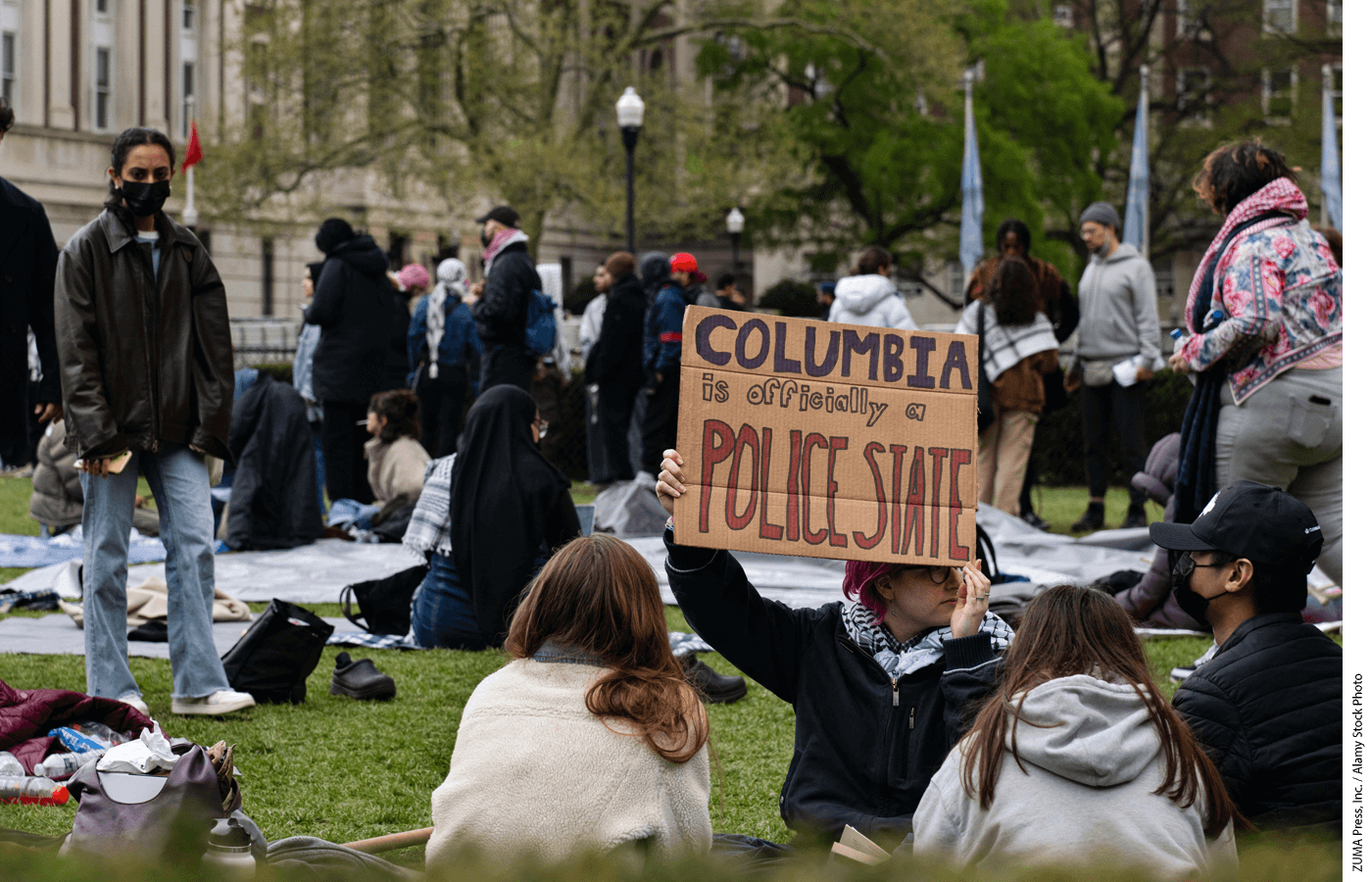

Columbia University scrapped in-person classes on Sunday after weekend demonstrations that the Biden White House described as “unconscionable and dangerous.” The New York Police Department eventually apprehended more than 100 protesters who had been part of the disorderly crowd singing “Hamas, we love you, we support your rockets too!” and transformed Columbia’s campus into a makeshift homeless enclave. The unrest was alarming but not unprecedented. Comparable events have sprung up nationwide, typically without repercussions. The arrests at Columbia stood out. They also underscore a recent pattern where authorities at other institutions, like Vanderbilt University, Washington University in St. Louis, and Pomona College, finally took action they should have taken earlier: impose consequences on the troublemakers who occupy campus structures, incite violence, deface property, and intimidate their peers.

Observing Columbia’s turmoil unfold over the recent days, I couldn’t help but evoke a past incident in the university’s past: the public letter penned to the institution’s then-president in 1968 by Mark Rudd, the campus leader of Students for a Democratic Society, the day before Columbia’s renowned student uprising. As Rudd succinctly expressed at the time: “Up against the wall, motherf—–, this is a stick-up.”

Present-day campus protests exhibit a lot of desire, ego, and showmanship. Drawing inspiration from the cultural reminiscence of Rudd and his fellow ’60s-era performers, they are dramatic events rather than thoughtful ones. They prioritize theatrics over introspection. In fact, they appear designed to impede reasoned dialogue and serious investigation, making them ill-suited to esteemed institutions of higher learning. Nevertheless, many faculty members who privately worry about this phenomenon seem hesitant to voice their concerns. More troublingly, other scholars appear strangely unperturbed by the impact of campus disorder on the educational process. The proponents of chaos seem oddly indifferent to the educational value in their classrooms.

While the Vanderbilt episode unfolded, a couple of Carleton College professors—Amna Khalid and Jeffrey Aaron Snyder—finally reacted to a column I had penned late last year (academic schedules, you know). They wrote an extensive essay for the Chronicle of Higher Education defending, well, campus disorder. They took issue with my assertion that “the historical function of campus free speech is not to provide banner-waving protesters with a scenic backdrop, but to enable the unrestricted pursuit of truth and understanding in teaching, learning, and research.”

In their view, my comment that “there’s nothing particularly educational about the protests, letters, and rallies” aligns me with the “shut up and study” crowd. After numerous words, Khalid and Snyder ultimately circle back to criticize a point that I thought might offer a modicum of viewpoint-neutral common ground for advocates of free inquiry: that the primary aim of campus free speech is to protect “the freedom to inquire in classrooms, not the freedom to wave banners on the quad.”

Khalid and Snyder vehemently oppose that notion, arguing, “We reject the claim that the only worthwhile protests on campus are those that occur in science labs.” Alright then. They go on to explain that colleges have a “dual pedagogical mission” that includes fostering “critical-thinking skills” and “informed, engaged citizens,” and, as a result… well… frankly, it becomes unclear. They offer a plethora of words but little clarification.

Insisting that students learn about citizenship through protest (or by observing others), Khalid and Snyder contend that colleges should embrace such activities. They condemn institutions that have “tightened rules for student demonstrations,” state that “political protests are meant to provoke,” and declare that “the essence of a demonstration is to make a lot of noise and arouse people from their apathy.” However, their message becomes cloudy. They tentatively acknowledge that “some basic guidelines must be followed”—including no “targeted harassment,” no “heckler’s veto,” and allowance for time, place, and manner restrictions. The numerous contingencies somewhat complicate their endorsement of disruptive and provocative actions.

Setting aside these details, Khalid and Snyder emphasize that preparing for citizenship entails students “having [their] voice heard,” “advocating for positions dear to their hearts,” and acquiring “tactics,” “strategies,” and “when and how to make alliances and compromises.” They have certainly captured an aspect of citizenship, even if it’s unclear why any of it (particularly the tactics, alliances, and compromises) necessitates sit-ins or campus disruptions.

Subscribe to Old School with Rick Hess

Get the latest from Rick, delivered straight to your inbox.

Subscribe

Listen, as I’ve mentioned numerous times, saying “I want!” is actually the easy aspect of citizenship. It’s a tendency that emerges quite naturally, one that we all refine as children and adolescents. I doubt that assisting college students in channeling teenage egotism is the best way to prepare them for citizenship.

It’s rather odd to imply that our civic dilemmas stem from insufficiently indignant dissent. In a landscape marked by exaggerated social media, pro-terrorist performances on campus, and theatrical politicians in the U.S. House of Representatives, do we truly believe that America’s issue is a lack of activism?

Having been a high school civics teacher at one point, I fully appreciate the need to educate students for democratic citizenship. However, democratic participation entails much more than activism and voting. It also includes responsibility, respect for regulations, patience, discernment, and a willingness to collaborate with those holding differing views.

These are the democratic values that students ought to absorb in classrooms, seminars, and public forums. These are serious, individual virtues; they are cultivated not by joining a slogan-chanting crowd but by individuals having the chance to absorb, listen, converse, and think. (I understand, you can practically sense the hegemonic oppression…)

Colleges that take these values seriously would equip students for activism grounded in facts, informed perspectives, and self-awareness—and quite possibly, more likely to have an impact beyond social media. Unfortunately, there is nothing about higher education today that instills confidence in that regard. Furthermore, the rallies, occupations, and accompanying intimidation have corroded the kind of thoughtful dialogues that foster sound citizenship.

We nurture citizens by teaching young people to listen, learn, reflect, and then express their opinions as autonomous individuals. Democratic citizens should be taught to think and speak independently, for themselves. Instructing students to spew venom from the safety of a smartphone or a crowd is the antithesis of that.

Historically, learning to be part of a masked, faceless crowd has not fostered democrats but has engendered authoritarian thugs. “Up against the wall, motherf—–,” indeed.

Frederick Hess is an executive editor of Education Next and the author of the blog “Old School with Rick Hess.”

The post Campus Thuggery Is No Way to Cultivate Citizens appeared first on Education Next.